It’s sometimes claimed that the Hillsborough Tragedy was the catalyst for the creation of football’s Premier League in 1992. In fact, as this latest draft extract from my forthcoming book ‘Where’s The Money Gone?’ reveals, threats by wealthier clubs to break away from the EFL and create a new competition had been evolving for years before the tragedy which claimed the lives of 97 Liverpool supporters.

In the 1980’s most football clubs were still run by small town businessmen - local lads made good who had no vision beyond next week’s result.

League President Jack Dunnett, a time-served backbench Labour MP, was emblematic of the old guard swept aside by Dein’s new broom.

After interviewing Dunnett about the crisis engulfing the League for my fanzine ‘Off The Ball’ in late 1987, I described his responses as “a cocktail of caution and ambiguity, laced with evasiveness”.

He had mastered the politician’s art of talking at length while saying nothing of value.

Dunnett’s successor as League President, Blackburn Rovers chairman Bill Fox, was equally out of his depth once it became clear the big clubs were serious about their threat to quit.

That said, it’s hard to imagine any compromise that might have been reached by this stage that would have satisfied them.

They had been chipping away for years at the solidarity which underpinned The Football League.

Arguably the most important was the abolition in 1983 of a long-standing arrangement which gave 20% of gate revenue from every match to the away club.

It was a practice which dated back to the earliest days of the professional game.

The first official rules of the EFL published in 1889 declared that “each club shall take its own gate receipts, but shall pay its opponents a sum of £12”.

This was formal recognition that while supporters might go to watch ‘their’ club, the game cannot exist without an opposing team. You might have a concert with just one headline act, but there’s no football match without a support act.

In that sense, revenue sharing wasn’t a ‘handout’ but a proper distribution of the profits from an event in which two equally important entities took part. (Incidentally, this principle still applies to FA Cup matches, but not to league games).

It also ensured that richer, better supported clubs helped sustain their less affluent rivals, generating a relatively equal competition.

Academics who studied the progress of 2,000 players before and after the rule change concluded that the abolition of revenue gate sharing “brought about increased rates of transfers of quality players towards top division teams.”

There was also “an increased probability that better quality players will be transferred within divisions to bigger teams.”

You don’t say. This, of course, was entirely the point of scrapping it.

It was one signifcant ‘play’ in a long game, which rumbled on throughout the 80s. Back page headlines carried dire threats of a ‘breakaway’ unless smaller clubs submitted to the will of larger ones.

The big clubs felt that as they generated the wealth of the game - through larger attendances and TV income - they should keep more of it for themselves.

Advocates for the continuation of a 92 clubs league argued that the entire ecology of English football - sporting, social, financial - would flourish better if it stayed true to its more co-operative roots.

It was the money men who won, of course. A favourite phrase at the time was that “we can’t have the tail wagging the dog”.

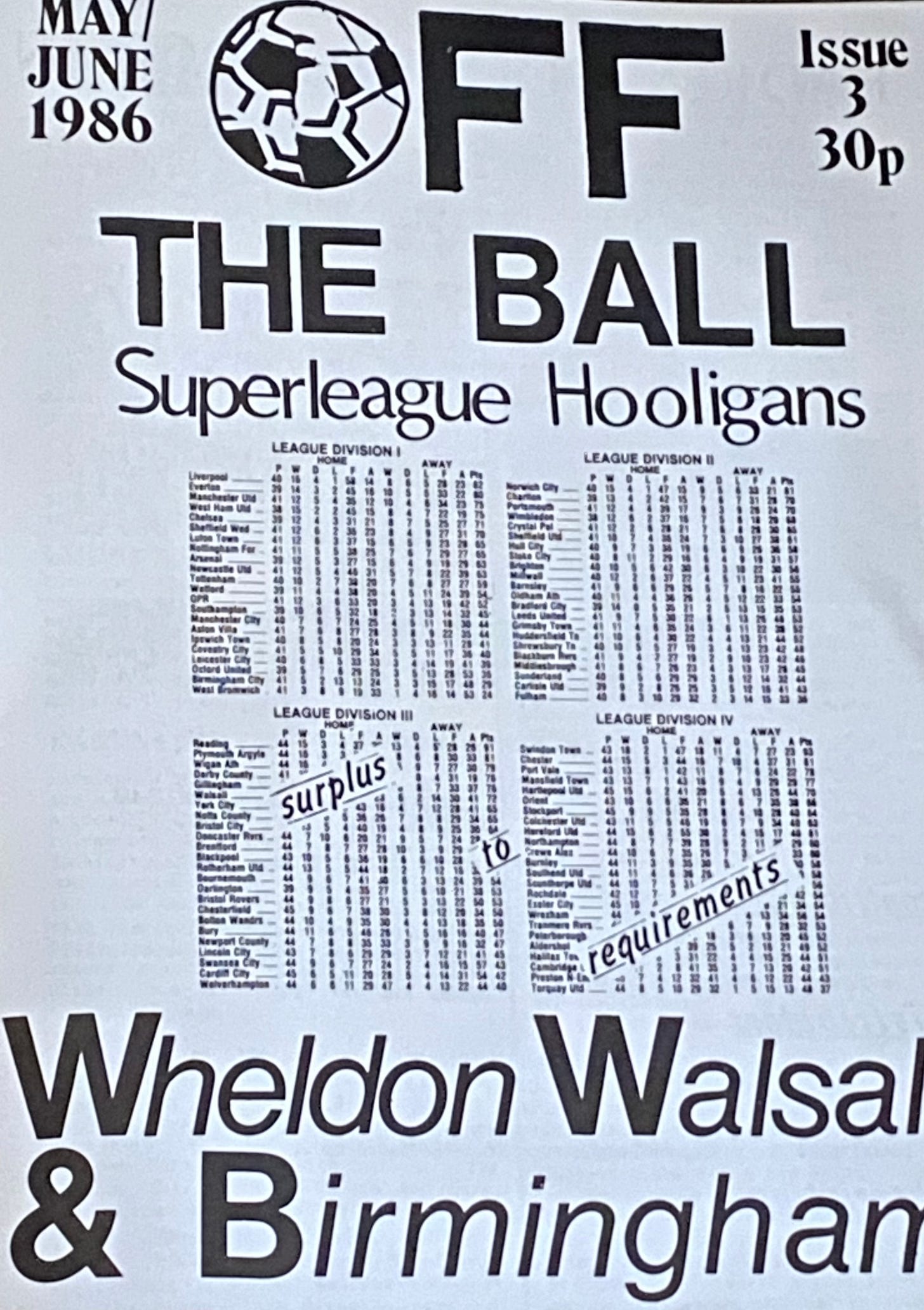

In 1985, four years before Hillsborough, my fanzine ‘Off The Ball’ was created in explicit opposition to the creation of a separate, breakaway league.

In February 1986 for Issue 2, I interviewed Manchester United director Maurice Watkins at Old Trafford on a chilly afternoon when Danish winger Jesper Olson went on the rampage, scoring a hat trick against West Brom.

It seemed as though mega rich United were looking to destroy the rest of the Football League in much the same way.

Watkins talked about the need to reduce the voting rights of smaller clubs, and allowing United and their ilk to keep more money from shared ‘pots’ like the FA Cup.

He warned: “If these very moderate proposals don’t go through, then there is a danger that some clubs will seek to form a breakaway”.

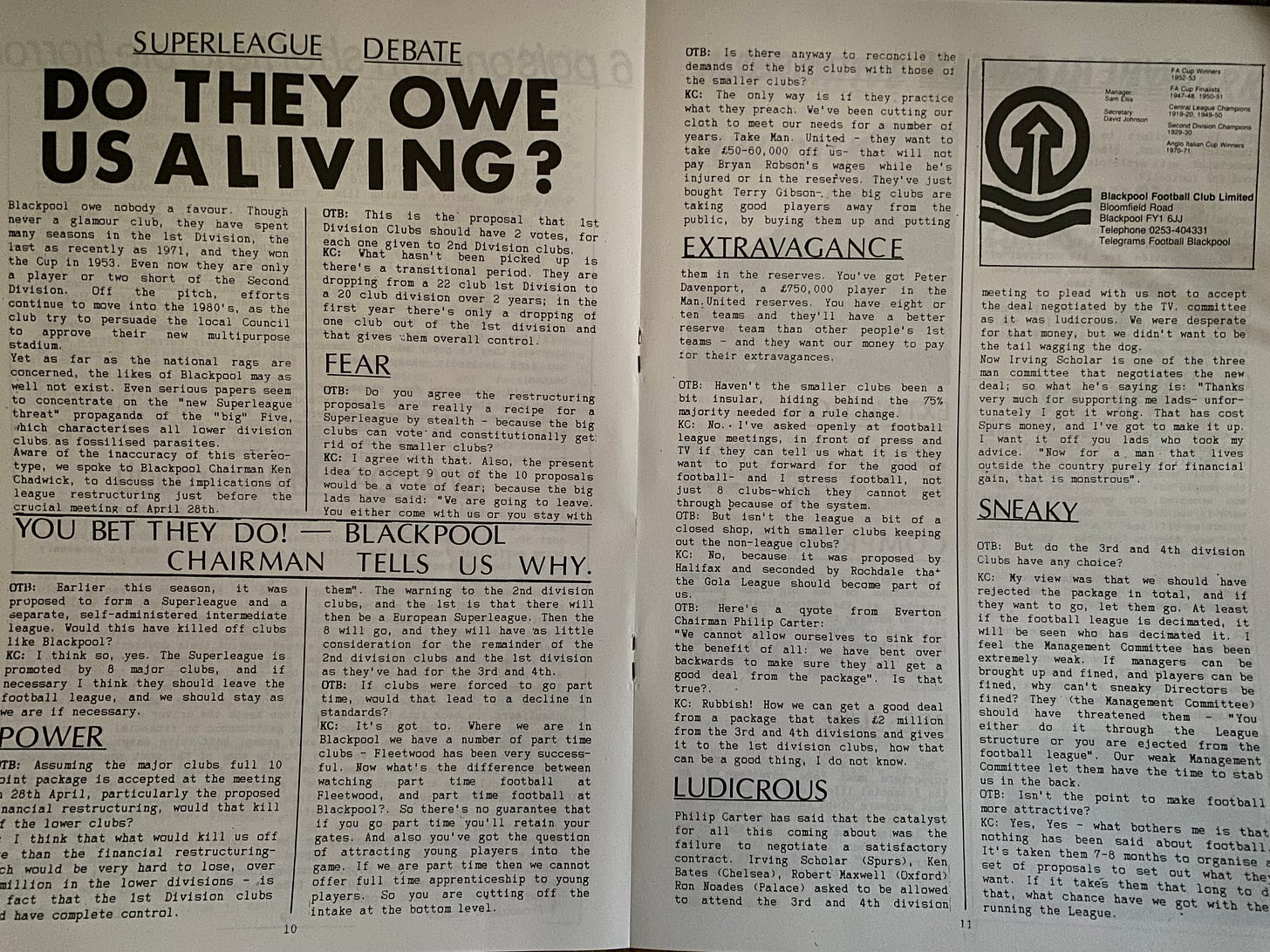

For the next issue in May 1986, I interviewed Blackpool chairman Ken Chadwick in the shadow of the gas holders at Bristol Rovers’ old Eastville Stadium.

Chadwick was vehemently opposed to a restructuring which would have granted more voting rights (and therefore extra money) to the bigger clubs, and called for the rebels to be expelled.

“I feel the League Management Committee has been extremely weak,” he said.

“If managers can be brought up and fined, and players can be fined, why can’t sneaky directors be fined?”

He said that the clubs threatening to head for the exit had “stabbed us in the back.”