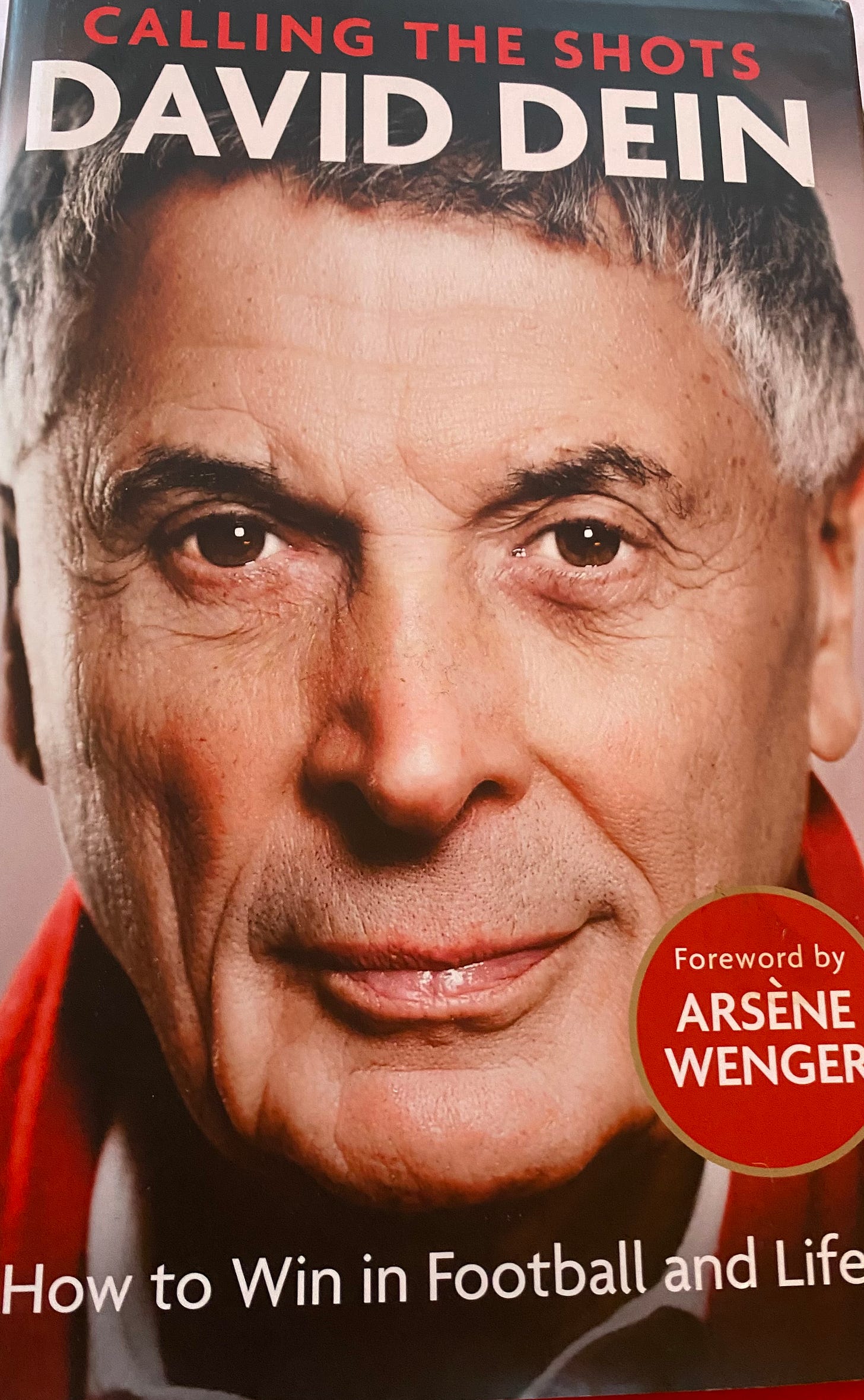

This is a short draft extract from a chapter of my forthcoming book ‘Where’s The Money Gone?’ where I meet David Dein, prime mover to the Premier League. The picture is the cover of his book ‘Calling The Shots’ written with Henry Winter, which I’d recommend. To read the rest of the chapter as it unfolds and other drafts, don’t forget to subscribe.

I push the buzzer a couple of times and a housekeeper welcomes me in.

There’s a large, open plan kitchen to my right, but I’m swiftly ushered through the hallway up a narrow spiral staircase.

We emerge into an airy lounge adorned with colourful modern artworks, family photos and souvenirs of a life in football.

White furniture. Not a place for young kids.

We’re on the most expensive square of the Monopoly board, in David Dein’s townhouse.

Arsenal’s former vice-chairman, has obviously done well for himself.

This is a traditional property, tall and narrow, but walls have been removed and new windows installed so that light pours in from every angle. Conversions like this don’t come cheap.

Dein, the son of a London cabbie, built a successful business importing food to serve the capital’s burgeoning Caribbean and African population in the 60s and 70s, before turning his hand to sugar trading.

Investing in Arsenal didn’t hurt him either. He got in before the explosion of wealth in football and walked away with £75 million.

As I walk up the stairs, Dein is on his mobile, arranging a meeting. Busy, busy, busy. Wiry and energetic, he looks fantastic for a man approaching 80.

We’re here to talk about his role in creating the Premier League. From his perspective, it’s his crowning achievement; for supporters of my disposition, it’s football’s original sin.

I’m determined to give him a fair hearing.

Like a pair of kids trading football cards, we swap our early experiences of the game.

Dein grew up on the terraces, after being taken to Highbury by an uncle.

He stood first in the North Bank, before gravitating to the seats in the East Stand, and, finally, the boardroom. He describes it as “a dream come true”.

This was the early 80s, a tricky time for the game we both love. As Dein recalls, “attendances were dropping, clubs were losing money hand over fist, football was going down the drain.”

But what to do about it?

The ambitious Dein was quick to make connections, establishing links with senior figures at other elite clubs. After winning election to the Football League’s Management Committee, he became their unofficial representative.

He went to the US and compared the big match experience on both sides of the Atlantic. Seeing a live NFL game was an eye opener.

“My wife Barbara comes from the States, so we used to go there very often” Dein explained.

“That was a big inspiration for me, seeing the razzmatazz.

“They’re the best marketing people in the world. They know how to get the last dime out of a customer.

“I remember taking in my first NFL game, at Miami Dolphins. I didn't realise how good they were, but they were the top team at the time.

“I'm sitting with my late brother-in-law, trying to watch the game. While he's explaining the rules, all I can hear in my ear is ‘Hot Dogs, Coca Cola, Cold Beer, Hot Dogs, Coca Cola.’

“I said to the guy next to me, ‘don’t they feed you at home?’

“But you couldn't do that in English football at the time. You were lucky if you got a cup of Bovril at half time.

“I thought ‘we’ve got to do something different, to make it entertaining. We’re going to make it pleasant. Fun’.”

Few football fans of my generation would have objected to improved facilities. The lousy quality of matchday catering was one of the key complaints of the early fanzines, mine included.

Vastly overpriced hot dogs. Burgers made from meat of dubious origin. Toilets that were often little more than open air latrines.

Given the half-time queues, some male supporters on the terraces felt they might as well urinate where they stood.

I once witnessed a fan whipping out his dick and sending a fountain of piss cascading down the terracing in an under-populated corner of the Shed End at Chelsea.

The turning point for the game was the Hillsborough Tragedy in 1989, which Dein describes as “a huge wake up call.”