(pic by Sarlondunc using Creative Commons)

This is the latest extract from my forthcoming book. ‘Where’s The Money Gone' - A Football Finance Odyssey’. It starts at the point in 2002 where Wimbledon were relocated to Milton Keynes.

What happened to Wimbledon in 2002 was more than unfortunate; in the eyes of their supporters, it was theft. In stealing their football club, Milton Keynes had taken their history, their identity, their….everything.

There was only one consolation – timing. The move to Milton Keynes and the anger that accompanied it happened just as politicians were waking up to the importance of football as a cultural phenomenon.

It had been a long time coming. Throughout the 70s and 80s, football supporters were routinely caricatured in the press as illiterate, shaven headed thugs. Like the striking miners and print workers whose conflicts with the police came to define industrial relations in the 1980s, fans were seen as “the enemy within”.

This was one of the reasons me and a couple of mates started a football fanzine in late 1985. We knew there were articulate voices on the terraces, including our own, that were being ignored.

There were already a few, small club-based zines (City Gent at Bradford City, Terrace Talk at York) but ours, ‘Off The Ball’, was the first attempt to reflect national, structural issues affecting the game.

‘When Saturday Comes’ followed shortly afterwards, and before we knew it, we were in the midst of a full-blown indie publishing phenomenon.

There was a moment at the end of the 80s when it seemed as though EVERY club had a fanzine. Some had several.

My own club West Brom had both ‘Grorty Dick’ and ‘Last Train To Rolfe Street’. There were maverick publications like ‘5 to 3’ which was full of gross humour.

The fanzine movement laid the ground for success of Nick Hornby’s bestseller ‘Fever Pitch’, a funny, nerdy hymn to the game published in 1992.

Football’s renaissance was also aided by the Gazza factor.

Paul Gascoigne’s tears when he was cautioned during the 1990 World Cup semi-final in Italy made him a superstar. The English nation revived its love affair with the national team, accompanied by the cool soundtrack of Pavarotti and New Order.

These positive vibes continued when England hosted Euro 96, a largely trouble-free tournament that silenced the naysayers who felt sure that the arrival of thousands of supporters from overseas would lead to violence.

The Premier League had also emerged as a leading TV sports brand in the years following its creation in 1992. Subscriptions to BskyB and later Sky demonstrated that football had untapped financial potential.

Wealthy investors were quick to cotton on, buying shares in the biggest clubs and pumping money into the purchase of some of the world’s best players.

It reversed the trend of the late 80’s when English clubs had been banned from European competition following the Heysel Tragedy.

During that unhappy period, top players like Ian Rush, Gary Linker and Mark Hughes left to seek their fortunes overseas.

The newly wealthy English game was able to retain its stars and attract top overseas players like Dennis Berkgamp, Peter Schmeichel and Eric Cantona who brought a new dimension to the game.

There were newly developed all-seated stadia, too. Improved facilities attracted families and minorities who might otherwise have been reluctant to brave it on the terraces.

It was a slow process but by the mid 90s it seemed as though everyone loved football.

Wimbledon fan Dave Boyle recalls, “we’d been though the absolute nadir of the 1980s, and now there was money coming in to renovate the stadiums. Loads of clubs were flirting with becoming PLCs.

“By 1995/96 football, along with Britpop, had become part of ‘Cool Britannia’.”

The game’s new found commercialisation came at a price – one which many of its traditional supporters struggled to afford.

In the period between 1989 and 1999 ticket prices in the top division rose by 312%. The rate of general inflation, as measured by the Retail Prices Index, increased by just 54%.

Stadiums were certainly filling up again, but with a skew towards the middle classes, especially at the big London stadiums. Old Trafford and Anfield, traditional temples of prole culture, where once a man might have pissed where he stood to avoid the queues in the toilets, were not immune.

Overseas tourists started appearing in large numbers. Corporate seating boomed.

Plastic seats for plastic fans, you might say, but the cash was rolling in.

New Labour politicians certainly weren’t shy of embracing the Premier League and basking in its reflected glory. They were also shrewd enough to recognise that the game’s new found success alienated some its core voters.

What could be done to reconcile the burgeoning financial aspirations of the top clubs with the needs of the communities they served?

Within a few months of taking office, Blair commissioned an independent Football Task Force led by former Tory Minister David Mellor, emphasising his ‘big tent’ approach to politics.

This was a landmark moment. After years of using the tradesman’s entrance it was as though the game had finally been allowed through the front door of Downing Street.

Hitherto, politicians had been wary of getting too involved in the game, perhaps fearful of the sport’s tribal emotions and any backlash against perceived ‘interference’.

In the mid 1960’s Labour Prime Minister Harold upped his ‘man of the people’ quotient by watching games at Huddersfield Town, but few other incumbents of No.10 followed his example.

Wilson even commissioned Oxford University academic Sir Norman Chester to review the state of football from top to bottom.

Chester’s weighty, thoughtful tome was published in 1968, but ministers generally only intervened when disaster struck, as it did at Ibrox Park in 1971, Bradford City in 1985 and Hillsborough in 1989.

Each tragedy spawned a bulky report designed to prevent the next tragedy.

Margaret Thatcher, despite her much-vaunted ‘common touch’ had little comprehension of what football meant to millions of ordinary voters.

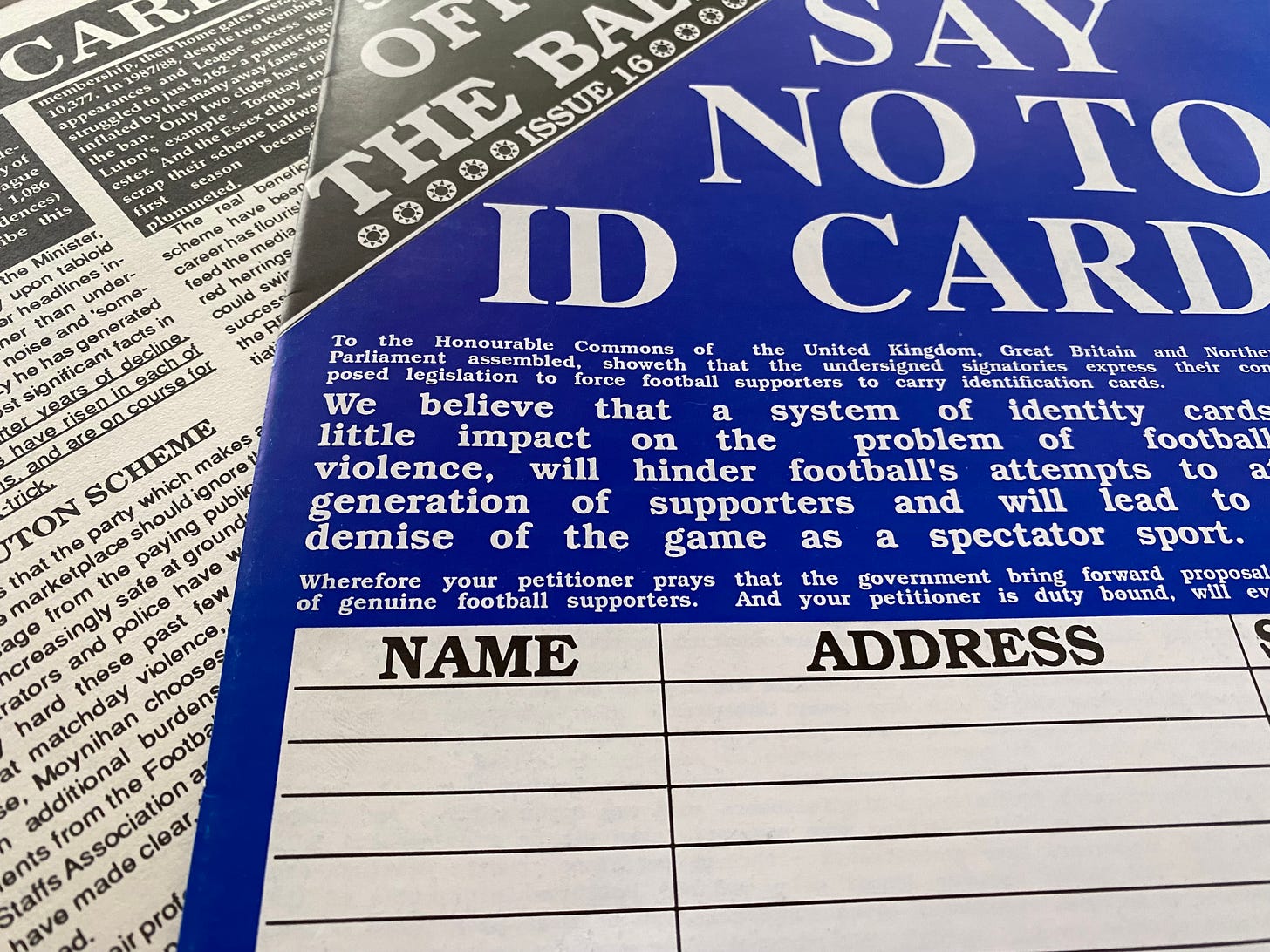

She appeared to see the game exclusively as a law and order problem and sought to make entry to every league ground conditional upon having a membership card which could then be withdrawn in the event of bad behaviour.

A version of the scheme was even trialled at Luton Town, then owned by Tory MP David Evans.

The “English Disease” was undoubtedly damaging to the country’s reputation abroad, but Thatcher’s prescription was hugely problematic.

Refuseniks like me called it an “Identity Card”, with all the Orewellian echoes that entailed.

Why pick on football fans, we asked, in a society rife with casual violence – some of it meted out by the police?

The infamous Battle of Orgreave in 1984, in which striking miners were indiscriminately bludgeoned by officers, came as no surprise to people who attended football every week. It sometimes happened to us, too.

We feared ID cards would kill off clubs already struggling with declining attendances. They felt like an authoritarian imposition on a sport that needed government help, not punishment.

Supporters across the country queued up to put their name to a petition which I launched with a few mates at the West Brom v Crystal Palace game in 1988.

The Football Supporters Association adopted the campaign with zeal, although only the deaths of 97 Liverpool supporters attending an FA Cup semi-final at Hillsborough a year later finally put paid to the legislation.

Even then, the mistrust and enmity between football supporters and the authorities lingered.

Blair’s election as PM provided the opportunity for a re-set.

Mellor’s Task Force travelled around the country, listening to fans complaints about admission prices, the cost of kits, ticket allocations for major matches and so on.

Much of what was said proved to be hot air, but the Task Force did make one truly significant recommendation. It called for the creation of an organisation to promote representation at board level for ordinary fans.

The government agreed and funded Supporters Direct, inspired by the success of Brian Lomax at Northampton Town.

Lomax had created the first Supporters Trust, a democratic, fan-owned, non-profit organisation when it became clear that The Cobblers were heading towards financial oblivion in the early 90s.

Deborah Marshall, who called a public meeting with Lomax in response to the crisis remembers that, “we had bucket collections and initially, the club were behind it, because they thought the money was going to go straight to them.

“They allowed the collections inside the ground.”

The Trust, though, had no intention of bailing out the hapless McArthur. They were building up their own war chest for when the inevitable happened, which led to Lomax being forcibly ejected by the Chairman.

In April 1992, Northampton went bust owing £1.6million.

“A guy called Barry Ward came in as administrator”, Marshall recalls.

“He and Brian got on really well and Barry saw the passion that Brian had got to keep the club alive.

“Brian had this idea of Northampton Town as a community asset and as a supporters’ asset rather than a businessman’s plaything.”

The traditional “white knight” who arrives on a charger to save a struggling club was nowhere to be seen, giving the Supporters Trust the opportunity to make a decisive intervention.

“I think without Brian being involved I honestly believe Northampton would have folded,” Marshall observes.

Supporters Direct was created a decade later was to help other clubs emulate what Lomax had done.

Dave Boyle was the organisation’s first direct employee, starting off as a case worker before rising to become Chief Executive.

He says, “it happened in many places previously that fans had raised money and helped save their club from administration or insolvency - in the 80s, Middlesbrough and Bristol City spring to mind.

“But in this particular instance at Northampton, the fans said, ‘No, we're not just going to give you the cash, we're going to buy some shares to protect our investment, because our money is as good as yours.”

Having worked closely with the administrator to save the club, The Supporters Trust helped steady the ship. That made the club attractive to outside investors again, but the Trust was granted two seats on the board.

A couple of years later, they worked closely with the local council to develop a new stadium at Sixfields.

Boyle explains, ‘this kind of partnership appealed very much to New Labour's ‘can't we all get along?’ kind of politics.”

Around the same time as Supporters Direct was created, the Blair government was also setting up the Co-Operative Commission.

The Commission sought to develop ‘mutual’ businesses, modelled on the 19th century movement which encouraged consumers and employees to become members of the businesses where they shopped or worked.

These stakeholders would have a democratic say in how the company was run, and how its capital was spent.

It seemed like the ideal alternative to football’s traditional ownership model for those fans who felt they could do a better job than their owners – which was, frankly, most of us.

“Brian Lomax wasn't doing what he did at Northampton from a background in the cooperative movement,” Dave Boyle explains, “but people within the co-operative movement said, ‘this is actually very similar to what we do.

“Wouldn't it be good if this kind of thing could be promoted a bit more?’”

Lomax was happy to evangelise, promoting Supporters Trusts around the country, and what started as a practical solution at one club became a movement.

Supporters Direct was born of this moment in time. The Task Force seized upon the notion of creating an organisation dedicated to encouraging greater fan participation in football boardrooms.

Given the vast sums of money involved at the top end of the game, this idea was most likely to have serious impact at lower division clubs where fans’ collective financial clout would be more powerful.

When Supporters Direct was created in 2000, Boyle says “our main business was dealing with clubs where the owners had been idiots and just walked off into the sunset leaving a car crash.

“Or where there were dodgy bastards coming in because they were looking to asset strip, by controlling a club’s land and maybe building houses on it.

“There were cases of out and out and gangsters, too, where people just loved the fact that football was a cash business and they could steal a bit.”

Dave’s workload exploded in March 2002 when ITV Digital collapsed. The broadcaster went bust 12 months into a three-year deal with the Football League, owing around £180million.

This was disastrous news for clubs in the Championship, League One and League Two. They had made investments in developing their stadia and given long term contracts to players in the reasonable expectation of that income.

Boyle says his work in the years that followed was ‘supercharged’. Clubs who were already operating at the limit of their financial constraints found themselves pushed over the edge.

The League was haunted by the ghost of League Two Aldershot FC, who’d gone bust in March 1992, forcing all of their previous fixtures that season to be scrubbed from the record.

Two months later Maidstone United managed to complete the campaign before they, too, were liquidated.

It looked like many more would follow in the aftermath the demise of ITV Digital.

Boyle says, “I'm absolutely convinced that if it wasn't for the work of the Supporters Trust movement and Supporters Direct, about 20 clubs would have not been there to fulfil their fixtures over the course of the next season”.

Although a replacement broadcasting deal was signed with Sky, the Football League’s TV income dropped by two thirds. Over the next couple of years, 17 clubs went into administration, including Leicester City who had debts of £30million.

The club was saved by a consortium of investors including the newly formed Foxes Trust, a fans’ group which raised £151,000 and bought a 2.5% share of the new company.

Boyle explains, “in most businesses, the administrators say ‘there's a lot of salary costs here, let's sack all the all the staff and build it back up, but you can't do that in football. You can't sack the players, because their union, the PFA, won’t allow it.

“Fans groups were raising money to help keep the clubs lights on during the period of administration. If that hadn’t been there, the administrators would have been responsible themselves.

“That’s a massive pressure on them to just close the business down.

“Everyone knows that there's a market for a football club in Leicester. Of course there is. The question was ‘could you keep the club alive long enough for the administrators to do their work and restructure the debts.”

The fans who did that were well rewarded 15 years later, when The Foxes won the Premier League title – albeit by then having acquired with the backing of one of the richest men in Thailand.

It was a similar story at Wrexham. The North Wales club was saved by a Supporters Trust, assisted by Boyle and his colleagues, long before Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney delivered their Hollywood ending.

League One Exeter City and League Two Newport County are both now majority owned by their fans. The SD model has adopted by clubs such as Rochdale Hornets in Rugby League, and even by Spanish soccer club Oviedo when they faced bankruptcy.

And then there was Wimbledon.